Structures and classes are general-purpose, flexible constructs that become the building blocks of your program’s code. You define properties and methods to add functionality to your structures and classes using the same syntax you use to define constants, variables, and functions.

Simply put your application uses structures and classes to build UI, business logic, and add functionality using structs and classes. So it will make sense for developers to understand how Swift handles memory allocation to a structure and a class.

Unlike other programming languages, Swift doesn’t require you to create separate interface and implementation files for custom structures and classes. In Swift, you define a structure or class in a single file, and the external interface to that class or structure is automatically made available for other code to use.

In this post, I will explore similarities, differences, and other things related to structures and classes in Swift. I will try and explain how memory management works for reference and value types in Swift. Consider this a basic explanation. I will explain more about memory management in my future post on ARC.

Structures and classes in Swift have many things in common.

Both can:

- Define properties to store values.

- Define methods to provide functionality.

- Define subscripts to provide access to their values using subscript syntax.

- Define initializers to set up their initial state.

- Be extended to expand their functionality beyond a default implementation.

- Conform to protocols to provide standard functionality of a certain kind.

Basically, what Apple means is structures and classes have a similar syntax definition. You introduce structures with the struct keyword and classes with the class keyword.

Example of a Structure in Swift :

struct Avenger {

var name: String

var powers: [String]

var goToWeapon: String

var color: Color

func costumeColor() {

print(color)

}

}

var avenger1 = Avenger(name: "thor", powers: ["sparkles", "fly"], goToWeapon: "Hammer", color: Color.red)

func print<T>(address p: UnsafeRawPointer, as type: T.Type) {

let value = p.load(as: type)

print(value)

}

withUnsafePointer(to: avenger1) {

print("Address location for instance avenger1 - \(String(format: "%p", $0))")

}

// prints Address location for instance avenger1 - 0x7ffee39eb628

print(avenger1.name) // prints thor

Example of a simple Class in swift :

class Xmen {

var name: String

var powers: [String]

var goToWeapon: String

init(name: String, powers: [String], goToWeapon: String) {

self.name = name

self.powers = powers

self.goToWeapon = goToWeapon

}

}

var xman1 = Xmen(name: "deadpool", powers: ["talk", "swords", "gymnastics"], goToWeapon: "sword")

print(xman1.name) // prints deadpool

print("Address location for Object xman1 - \(Unmanaged.passUnretained(xman1).toOpaque())")

//prints Address location for Object xman1 - 0x0000600003662800

Why are Xmen a class? I mean they are X-Men: First Class(2011) after all 😉.

Whenever you define a new structure or class, you define a new Swift type. So, Avengers and Xmen are swift types just like a String or Int.

Give types UpperCamelCase names (such as SomeStructure and SomeClass) to match the capitalization of swift standard types such as String, Int, and Bool, etc.

Classes have additional capabilities that structures don’t have:

1.Inheritance enables a class to inherit the characteristics of another.

class Mutant {

var category: String = " "

}

class TheBrotherhood: Mutant {

var name: String = " "

var powers: [String] = [ ]

var goToWeapon: String = " "

let costumeColor: Color = Color.black

}

// Now our class TheBrotherhood can inherit the member types of Mutant class.

//init() is not needed because all the variables have default values in the declaration. //Swift initializes the class even with null values before an actual object is created.

2.Type casting enables you to check and interpret the type of a class instance at runtime.

3.Deinitializers enable an instance of a class to free up any resources it has assigned. It performs any custom cleanup just before an instance of that class is deallocated.

4.Reference counting allows more than one reference to a class instance.

5.If you do not assign values to your variables and constants in class, you need to explicitly initialize the members using the init( ) method.

Swift also allows you to assign default values to the variable definition and by assigning default values, you can avoid the init() method of its members in the class or struct definition.

6.Unlike structures, class instances don’t receive a default memberwise initializer.

Differences

In all my Swift-related posts I tried to explain value type and reference type vaguely. So I decided to dig a little deeper and tried explaining how RAM works in IOS devices. I cannot emphasize enough how important this concept is to become better at developing robust applications using Swift.

Before we get into differences, let's discuss an important concept called Memory.

Memory Address

Although Swift intelligently uses ARC for memory management, It is crucial for developers to know the concept of Memory and how is it used by Swift to assign to its types.

Your devices have a crucial component called RAM (Random Access Memory), which is used to store working data when you are using the device.

RAM is your memory. It's referred to as a volatile medium because it handles active processes and not static ones. For example, iPhone RAM handles processes like apps, a browser with 20+ tabs open while listening to the music app or your favorite podcast app, then open a text from a friend on some other messaging app when you receive a notification, etc so it's a volatile memory and changes dynamically.

If you haven't used an app on your device for a while, iOS pretty quickly kills any background processes in RAM so that performance doesn't deteriorate unless you have background app refresh on for that application.

Consider RAM as a workspace the device uses to get work done.

RAM/memory divides its space into discrete chunks (multiple 1-byte spaces), and each chunk has a unique memory address.

Memory is just a long list of bytes.

The bytes are arranged orderly, every byte having its own address.

A range of discrete addresses is known as an address space.

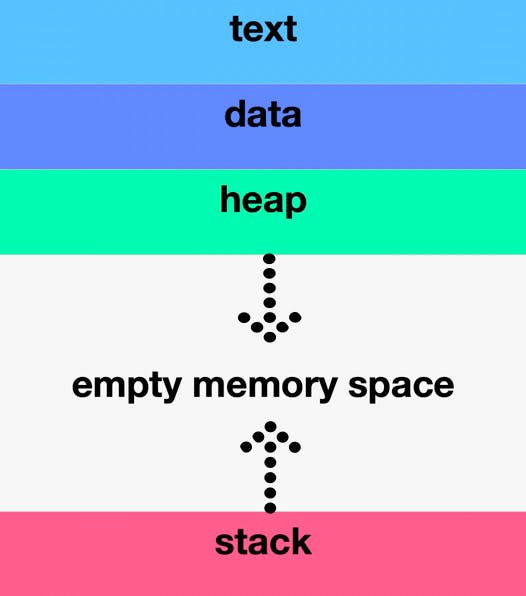

The address space of an iOS app logically consists of four segments:

text

data

the stack

the heap

The text segment contains the machine instructions that form the app’s executable code. It is produced by the compiler by translating the Swift code into machine code. This segment is read-only and takes constant space.

The data segment stores Swift static variables, constants, and type metadata. All global data that needs an initial value when the program is started goes here.

The stack stores temporary data: method parameters and local variables. Every time we call a method, a new chunk of memory is allocated on the stack. This memory is freed when the method exits. With some exceptions, all Swift value types go here.

The heap stores objects that have a lifetime. These are all Swift reference types and some cases of value types.

In Swift, value types are assigned to the stack during compile-time and the heap memory is allocated to reference types during the application runtime. This is one reason why Swift compiler expects you to initialize all the member types of a class or a structure.

Image - address space of a single thread in a process.

The memory of the stack and heap extend towards each other as shown in the image above.

Now let's discuss how Stack and Heap work.

The stack and heap from memory are allocated similarly based on how these data structures work.

Memory address usually is a hexadecimal string (eg: 0x12345) in most devices.

When the CPU needs to get data from a certain chunk of memory, it will reference the memory address.

This concept is called a Pointer in Computer Science.

When we declare variables in Swift/Objective-C, the operating system will allocate a chunk(chunks) of memory (with memory address) to store them.

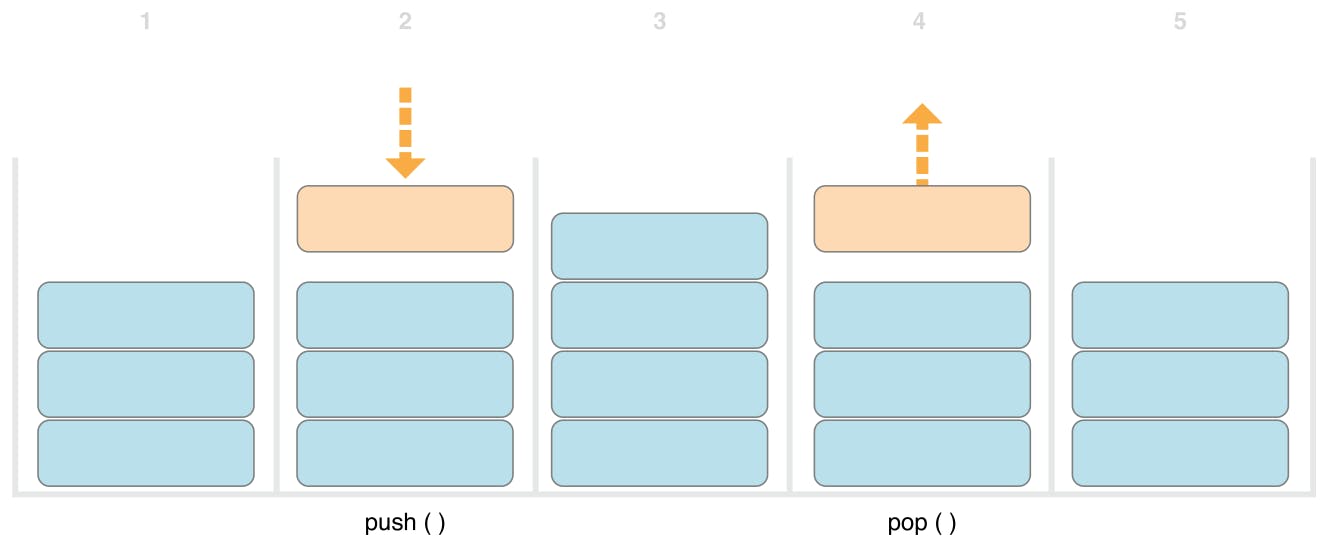

Stack follows LIFO - "Last In First Out" approach while allocating memory.

Stack is a data structure with two operations push and pop.

A pointer to the top of the stack is enough to implement both operations, so we just need to increment or decrement the pointer when a new allocation or deallocation occurs.

Stack Allocation is a simple and fast way to allocate/deallocate memory. It impacts a lot when it comes to performance.

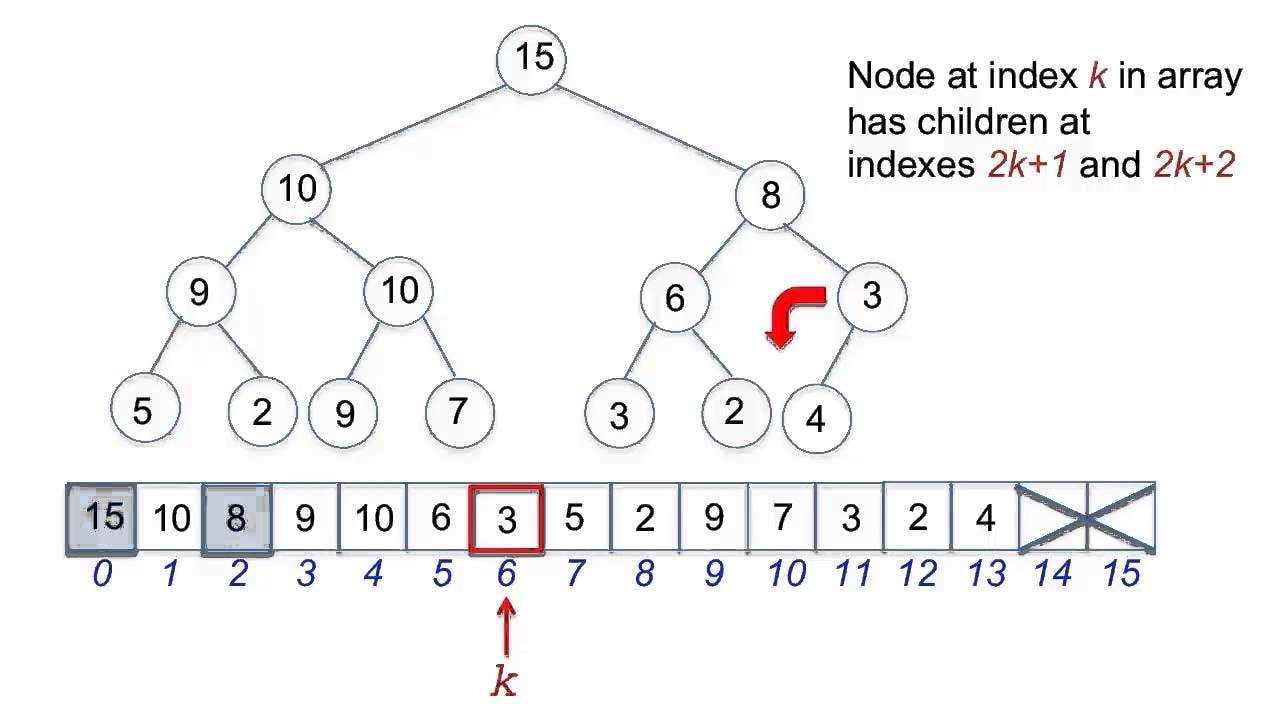

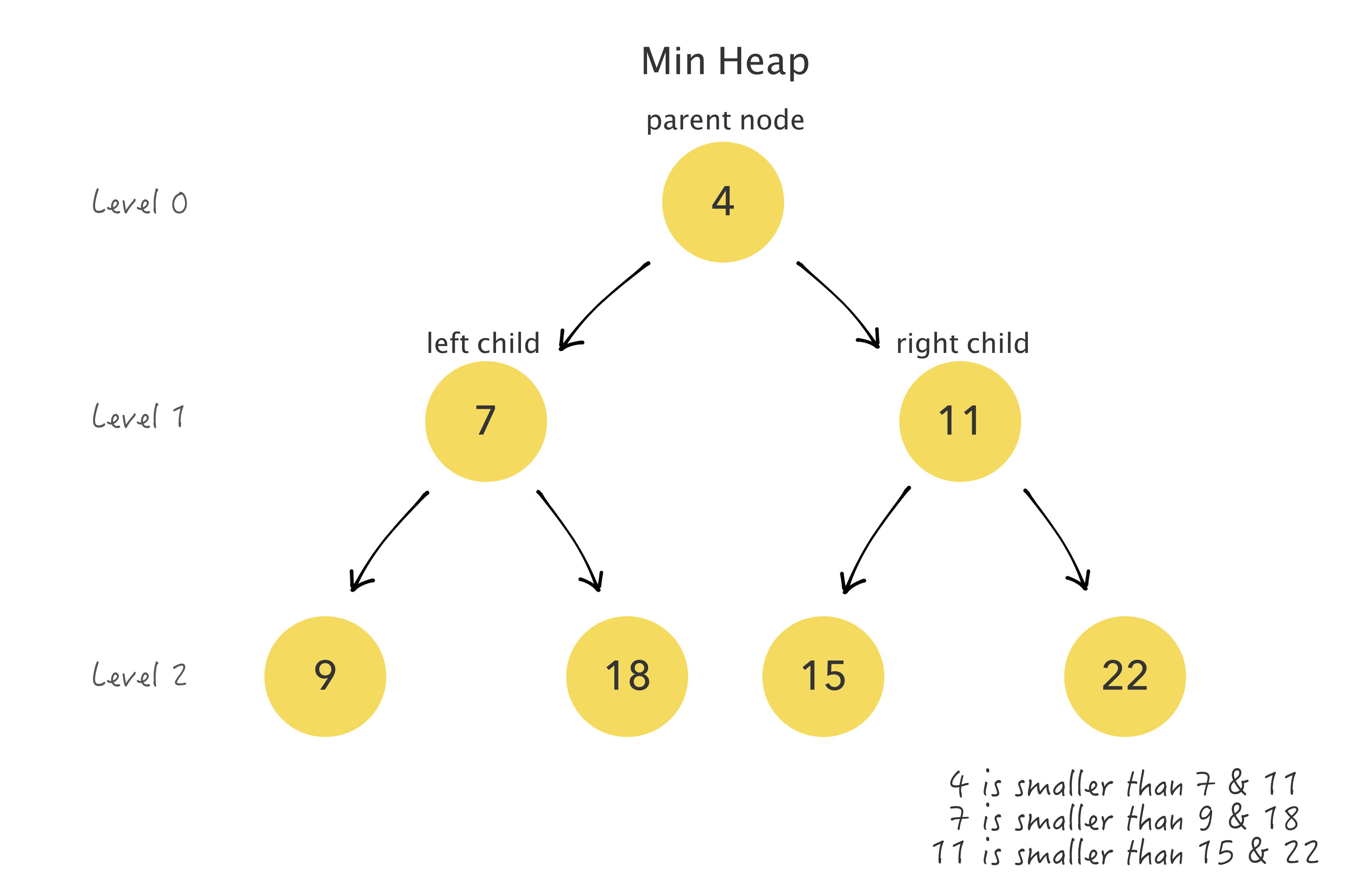

Heap is a specialized binary tree-based data structure.

All of the nodes in the tree have 0, 1, or 2 children.

There is more involved in the heap allocations.

The compiler has to search the heap data structure to find an empty block of memory of the appropriate size.

It also has to synchronize the heap, since multiple threads can be allocating memory there at the same time.

To deallocate memory from the heap we have to reinsert that memory back to the appropriate position.

The Heap data structure can be used to efficiently find the nth smallest (or largest) element by assigning a priority in an array.

The best part is under the hood a heap is stored as an array and the indexing works like in the below image.

Example of a maxHeap data structure.

Example of minHeap

Heap allocations and deallocations costs are way larger than the stack ones. Heap allocation is slower than Stack allocation not just because of the more complex data structure - it also requires thread safety.

In a multi-threaded situation, each thread will have its own completely independent stack but they will share the heap.

Stack is thread-specific and Heap is application-specific. The stack is important to consider in exception handling and thread executions.

Structures, Arrays, Sets, Dictionaries, Enums, Tuples, in fact, every type except Class, Function, and Closure is a value type and Swift value types are allocated memory on the stack with some exceptions of course.

Under the hood all the value types in Swift are implemented as structures.

Reference types like Class, Function, and Closure are allocated memory on the heap. In some cases, they are assigned to the stack as well.

I will discuss these exceptions in my next post on ARC.

Note: Compiler does a lot of optimization in different phases. Sometimes we don’t know whether we are actually using a value type or a reference type.

The performance differences between the two are expressive and can heavily favor one or another depending on the contents of your object, especially when dealing with value types.

Basics of ARC in Swift.

ARC is a compile-time feature. The compiler inserts the necessary retain/release calls at compile-time, but those calls are executed at runtime, just like any other code.

Memory management is the way of controlling memory allocation and making it free/available for other processes to use. Automatic Reference Counting is the mechanism used for it in iOS.

How ARC works?

Every time we create a new instance of a class, ARC allocates a chunk of memory to store information about that instance.

This memory holds information about the type of the instance, together with the values associated with that instance.

The name by which an object can be pointed is called a reference.

Reference counting applies only to instances of classes.

Reference count determines when an object is no longer needed.

This counter gets incremented by one for every new reference to the instance. When it becomes zero that means the object is no longer needed.

The object then deinitializes and deallocates.

Swift references can be of two types: strong and weak.

We will discuss ARC more in-depth in my next post.

Now let's discuss the differences.

1.Structures are value types.

When you pass a value type to a variable, a copy of the existing instance is made. The new instance will have its own memory in the stack.

let avenger2 = avenger1

//now avenger2 object has a copy of avenger1 object.

print(avenger2.name) // prints thor

// Now try to change the "name" property in the object avenger2 and see if it affects the avenger1 object

avenger2.name = "hulk"

print(avenger1.name)

// prints thor

print(avenger2.name)

// prints hulk

func print<T>(address p: UnsafeRawPointer, as type: T.Type) {

let value = p.load(as: type)

print(value)

}

withUnsafePointer(to: avenger1) {

print("Address location for instance avenger1 \(String(format: "%p", $0))")

}

//Address location for instance avenger1 0x7ffee698e620

withUnsafePointer(to: avenger2) {

print("Address location for instance avenger2 \(String(format: "%p", $0))")

}

//Address location for instance avenger2 0x7ffee698e658

2.Classes are reference types.

They are passed around using pointers, a pointer to the heap memory location where the class is located.

var xman2 = xman1

//variable "xman2" is now pointing to the address location of "xman1" in the heap.

print("Address location for Object xman1 \(Unmanaged.passUnretained(xman2).toOpaque())")

//Address location for Object xman2 0x0000600003c54730

// xman1 and xman2 will have the same address and both objects are pointing to the same memory location now.

print(xman2.name)

// prints deadpool

xman1.name = "wolverine"

print(xman1.name)

print(xman2.name)

// both the statements print "wolverine".

//As the value is assigned to property "name" in that address location and both the objects xman1, xman2 are pointing to the same address location on HEAP.

3.Structs have no Inheritance.

You cannot inherit the features from other structures or classes but you can conform to a protocol.

struct Revenger: Avenger {

}

// The Swift compiler throws error -

// "Inheritance from non-protocol type 'Avenger' "

4.Classes in Swift have a single inheritance.

You can always use another class for inheritance. But swift does not support multiple inheritance. It allows single inheritance.

class TheBrotherhood: Mutant, Xmen {

}

// The Swift compiler throws error -

//"Multiple inheritance from classes 'Mutant' and 'Xmen'"

5.The struct has a memberwise initializer that initializes all the stored properties in a struct.

6.A structure instance can only be mutated if it’s defined as a variable and it will only update the referencing instance.

let revenger = avenger1

revenger.name = "valkyrie" // error

//Swift compiler throws error -

//Cannot assign to property: 'revenger' is a 'let' constant

//Change 'let' to 'var' to make it mutable

When a value type is declared as "let" the contents of it cannot be modified.

7.Value types do not need dynamic memory allocation or reference counting, both of which are expensive operations. At the same time methods on value types are dispatched statically.

This gives a huge advantage in favor of value types over reference types in terms of performance.

Now what? Should I use a Structure or a Class for my requirement?

Structure instances are always passed by value, and class instances are always passed by reference. This means that they are suited to different kinds of tasks. As you consider the data constructs and functionality that you need for a project, decide whether each data construct should be defined as a class or as a structure.

Swift provides a number of features that make structs better than classes in many circumstances.

Structs are preferable if they are relatively small and easy to pass a copy because copying is way safer than having multiple references to the same instance as happens with classes. This is especially important when passing around a variable to many classes and/or in a multithreaded environment. If you can always send a copy of your variable to other places, you never have to worry about that other place changing the value of your variable underneath you.

With structs, there is much less need to worry about memory leaks or multiple threads racing to access/modify a single instance of a variable. (For the more technically minded, the exception to that is when capturing a struct inside a closure because then it is actually capturing a reference to the instance unless you explicitly mark it to be copied).

Classes can also become bloated because a class can only inherit from a single superclass. That encourages us to create huge superclasses that encompass many different abilities that are loosely related. Using protocols, especially with protocol extensions where you can provide implementations to protocols, allows you to eliminate the need for classes to achieve this sort of behavior.

As a general guideline(Apple Docs), consider creating a structure when one or more of these conditions apply :

The structure’s primary purpose is to encapsulate a few relatively simple data values. Let's say a model in our application.

It is reasonable to expect that the encapsulated values will be copied rather than referenced when you assign or pass around an instance of that structure.

Any properties stored by the structure are themselves value types, which would also be expected to be copied rather than referenced.

The structure does not need to inherit properties or behavior from another existing type.

In all other cases, define a class, and create instances of that class to be managed and passed by reference. In practice, this means that most custom data constructs should be classes, not structures.

You should consider using a class when:

- Comparing instance identity is needed by using "===".

- A shared mutable state is required.

- Objective-C interoperability is required.

Ideally, you need to understand the real-world implication of value types vs. reference types and then you can make a decision about when to use structs or classes. It takes practice and I am still learning the use of structs and classes in swift.

Conclusion

Try to go for a struct by default. Structs make your code easier to reason about and make it easier to work in multithreaded environments which we often have while developing in Swift.

Also, if you do decide to go for a class, consider marking it as final and help the compiler by telling it that there are no other classes that inherit from your defined class.

Hopefully, in time you’ll be able to decide about choosing between a class or a struct. It’s definitely not always easy and possible to go for a struct but it should be considered the default when programming in Swift. Once you’ll use structs more often I’m pretty sure you’ll get used to working with them.