After writing about functions in my previous blogpost, I am inclined to discuss Closures next. After all, I generously used closures in many examples without understanding the nuances of the syntax. The syntax and its variations piqued my interest and pushed me to understand closures more. Swift uses closures extensively and pushes towards low code by cleverly implementing closures underneath. In fact every function is dealt as a closure while compiling a program in Swift. I had a really good time with closures these past few days and here is my experience with it.

What is a Closure?

- Closures are self-contained blocks of functionality that can be passed around and used in your code.

Think of a closure as a function that can be stored as a variable (referred to as a "first-class function"), that has a special ability to access other variables and constants local to the scope it was defined in.

- Scope is the region of the codebase over which an identifier is valid. I tried to explain more about the scope at bottom of this post with a reference blogpost. Do check it out.

You can pass a closure as an argument of a function or you can store it as a property of an object.

The name closure hints at one of the key characteristics of closures. A closure captures the variables and constants of the context in which it is defined. This is sometimes referred to as closing over those variables and constants.

Functions are considered as special cases of closures.

In Swift, a function (including a method) is semantically just a closure with a static name, you can pass a function name anywhere that a closure parameter is required, assuming that the type signature is correct. The compiler takes care of smoothing over the difference between "use" and "capture".

Are closures used in other programming languages?

Yes. Below is a list of a few of the programming languages that use closures in some form.

- PAL programming language.

- blocks in C, C++, and Objective-C.

- lambdas in Ruby are similar to closures.

- Java and javascript.

- Delegates (C#, VB.NET, D).

- Inline agents (Eiffel).

- Dart, Scheme, ML, Haskell, F#, Kotlin, Scala, PHP, Python, Raku, Delphi, Rust, etc use closures as first-class objects.

A first-class citizen/object is an entity in programming languages, which supports all the operations generally available to other entities. These operations typically include being passed as an argument, returned from a function, modified, and assigned to a variable.

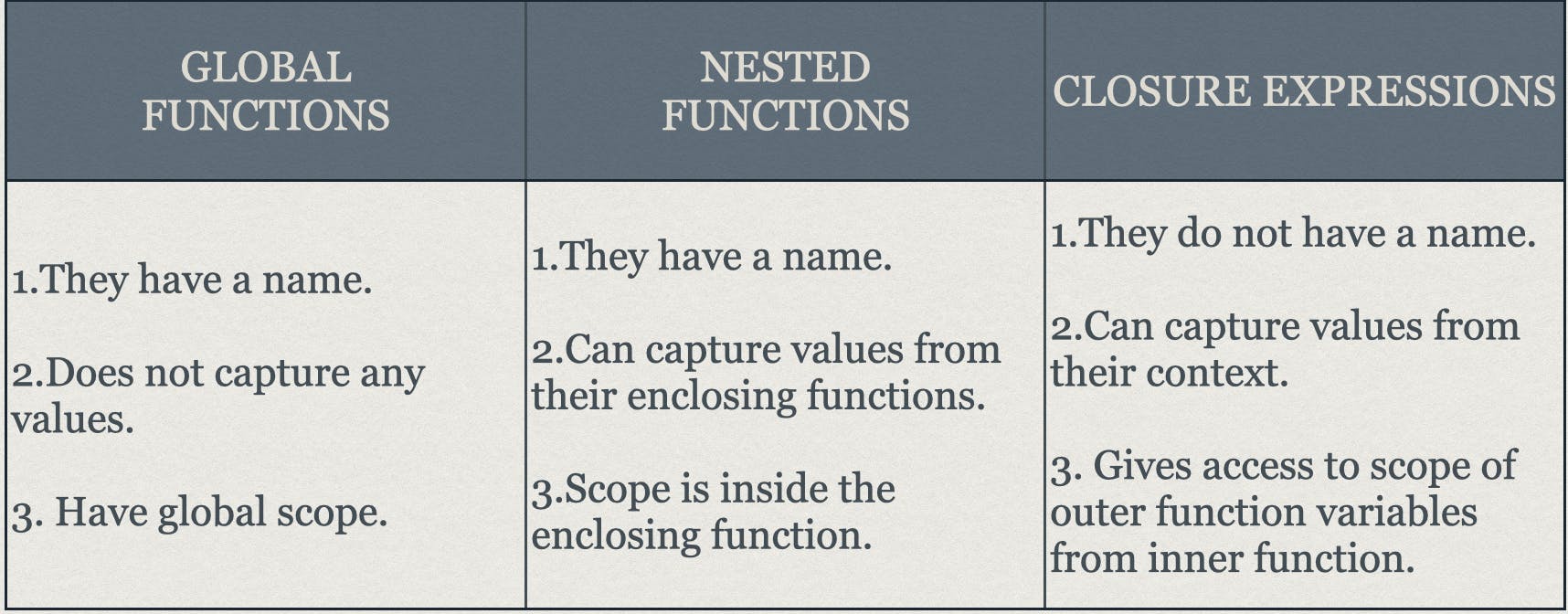

Closures takes the following three forms in SWIFT

Global functions, such as the print(_:separator: terminator:), captures no values.

Nested functions, however, have access to and can capture the values of constants and values of the function they are defined in.

Closure expressions, also known as unnamed closures, can capture the values of constants and variables of the context they are defined in.

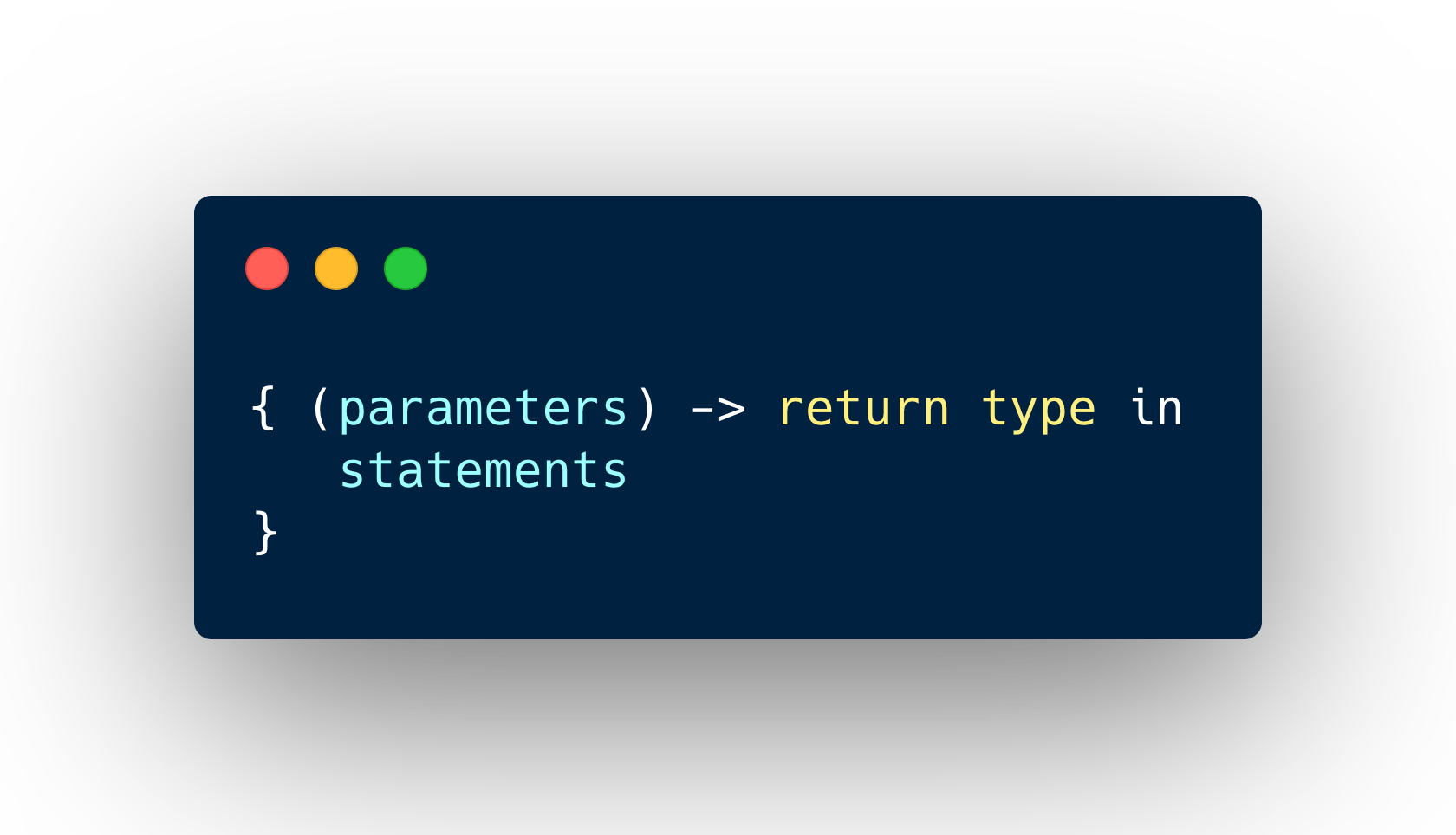

Syntax of a Closure in SWIFT

Parameters : Parameters in the closure are just like parameters in a function. A closure can have zero or multiple parameters, and they can be standard data types, like integers, strings, or custom structs and classes, as well as tuples.

return type : We need to specify the return type for a given closure. Like parameters, a closure’s returned data type is flexible too — standard or custom data types are both acceptable. In addition, the Void is also a valid return data type, which means essentially the closure body doesn’t need to return anything.

in keyword : The in keyword is used after defining the parameters and return data type of the closure and before the closure body. It separates the steps of execution from the declaration of parameters and return type in a closure body.

statements : statements are defined in the closure body after the in keyword, we write the code that uses the parameters and generates the return data.

The parameters in closure expression syntax can be in-out parameters, but they can’t have a default value. Variadic parameters can be used if you name the variadic parameter. Tuples can also be used as parameter types and return types.

I'll try to explain the syntax of Closure Expressions or a typical closure using a function and the below steps.

- Inferring Type From Context

- Implicit Returns from Single-Expression Closures

- Shorthand Argument Names

- Trailing Closures

Below is an example of a function to calculate the square of all the odd integers from an array of integers. I will try to simplify the same function using swift's higher order functions filter and map. We can achieve the same task using fewer steps in Swift using closures, and higher order functions are one concept in swift which uses closures effectively.

Example: Function which calculates the square of all the odd integers in a given array of integers.

var numbersToFilter: [Int] = []

numbersToFilter.append(contentsOf: 1...100)

// has first 100 natural numbers in the array

func calculateOddSquare(arrayOfInt: [Int]) -> [Int]

{

let tempArray = arrayOfInt

var oddSquareNumbers: [Int] = []

for index in 0 ..< tempArray.count

{

if tempArray[index] % 2 == 1 {

oddSquareNumbers.append(tempArray[index]*tempArray[index])

}

}

print("\(oddSquareNumbers)")

return oddSquareNumbers

}

calculateOddSquare(arrayOfInt: numbersToFilter)

// prints [1, 9, 25, 49, 81, 121, 169, 225, 289, 361, 441, 529, 625, 729, 841, 961, 1089, 1225, 1369, 1521, 1681, 1849, 2025, 2209, 2401, 2601, 2809, 3025, 3249, 3481, 3721, 3969, 4225, 4489, 4761, 5041, 5329, 5625, 5929, 6241, 6561, 6889, 7225, 7569, 7921, 8281, 8649, 9025, 9409, 9801]

Example: The same function simplified using closures.

var numbersToFilter: [Int] = []

numbersToFilter.append(contentsOf: 1...100)

// has first 100 natural numbers in the array

let oddSquareNumbers = numbersToFilter.filter {

$0 % 2 == 1 //select all the odd numbers

}.map {

$0 * $0 // square them

}

print(oddSquareNumbers)

filter method in swift is a higher order function from Standard Library which returns an array containing, in order, the elements of the sequence that satisfy the given predicate.

It takes a parameter, a closure that takes an element of the sequence as its argument and returns a Boolean value indicating whether the element should be included in the returned array.

map method in swift is also a higher order function from Standard Library which returns an array containing the results of mapping the given closure over the sequence’s elements.

It takes a parameter, a mapping closure that accepts an element of this sequence as its parameter and returns a transformed value of the same or of a different type.

Both of the methods take a closure as their parameter. I will try to show the variations of the syntax of closures in swift and deduce to map method closure syntax. I will explain the syntax variations of closure using the filter method. The perfect example with closure expression syntax is below, from which I will explain the syntax using filter method closure.

Example: The same function using closure expression syntax in filter method parameter.

var numbersToFilter: [Int] = []

numbersToFilter.append(contentsOf: 1...100)

let filteredNumbers = numbersToFilter.filter( { (number: Int)-> Bool in

return number % 2 == 1

} ).map{$0 * $0}

print(filteredNumbers)

The capture defined as a parameter in the parenthesis of filter method has a Type or Signature - "A closure/function which takes an integer as a parameter and returns a boolean value". Yes, you can pass a function to swift's higher order functions instead of a closure.

Inferring Type From Context

The compiler can infer/detect return data type, which means there's no reason to include it in the closure expression definition.

We can only do this if the closure's body includes a single statement, though. In that case, we can put that statement on the same line as the closure's definition, as shown in the below example.

Example: The same function by eliminating parameter type and return type in the closure.

var numbersToFilter: [Int] = []

numbersToFilter.append(contentsOf: 1...100)

let filteredNumbers = numbersToFilter.filter({ number in

return number % 2 == 1

}).map{$0 * $0}

print(filteredNumbers)

Because there's no return type in the definition and no -> symbol preceding the return type, we can omit the parentheses ( ) enclosing the closure's parameters.

Implicit Returns from Single-Expression Closures

Single-expression closures can implicitly return the result of their single expression by omitting the return keyword from their declaration.

Example: The same function by removing the return keyword in the closure.

var numbersToFilter: [Int] = []

numbersToFilter.append(contentsOf: 1...100)

// has first 100 natural numbers in the array

let filteredNumbers = numbersToFilter.filter({ number in

number % 2 == 1

}).map{$0 * $0}

print(filteredNumbers)

Shorthand Argument Names

In the closure body, we reference the arguments using shorthand argument names that Swift gives us. Rather than writing number (variable) in number, we can use Swift's automatic names for the closure’s parameters. These are named with a dollar sign ($), then a number counting from number 0 - $0, $1, $2, ... so on.

Example: The same function by using just the shorthand arguments.

var numbersToFilter: [Int] = []

numbersToFilter.append(contentsOf: 1...100)

// has first 100 natural numbers in the array

let filteredNumbers = numbersToFilter.filter({ $0 % 2 == 1})

.map{$0 * $0}

print(filteredNumbers)

The first argument is assigned to $0, the next to $1, and so on.

Trailing Closures

You write a trailing closure after the function call’s parentheses. It doesn’t take any arguments, and when it’s called, it returns the value of the expression that’s wrapped inside of it.

“When you use the trailing closure syntax, you don’t write the argument label for the first closure as part of the function call. ”

Example: The same function with the closure expression outside the parenthesis.

var numbersToFilter: [Int] = []

numbersToFilter.append(contentsOf: 1...100)

// has first 100 natural numbers in the array

let filteredNumbers = numbersToFilter.filter( ){ $0 % 2 == 1}.map{$0 * $0}

print(filteredNumbers)

If a closure expression is provided as the function’s or method’s only argument and you provide that expression as a trailing closure, you don’t need to write a pair of parentheses () after the function or method’s name when you call the function.

Example: The same function without the parenthesis and the closure after the filter method.

var numbersToFilter: [Int] = []

numbersToFilter.append(contentsOf: 1...100)

// has first 100 natural numbers in the array

let filteredNumbers = numbersToFilter.filter{ $0 % 2 == 1}.map{$0 * $0}

print(filteredNumbers)

All the examples above with different syntax will work on xcode without any errors. The final syntax in this example is the same as the Closure example on top. All the examples will print the same numbers like that in the Function example on top.

Operator Methods

There’s actually an even shorter way to write the closure expression. Swift’s String type defines its string-specific implementation of the greater-than operator (>) as a method that has two parameters of type String and returns a value of type Bool. This exactly matches the method type needed by the sorted(by:) method.

You can use a closure reversedNames = names.sorted(by: { $0 > $1 } ) or simply eliminate the shorthand arguments from the closure and use the operator to sort the array.

Example: A closure to sort an array of strings by simply specifying the operator method.

let titanNames = ["godzilla", "kong", "scylla", "muto"]

reversedNames = titanNames.sorted(by: >)

print(reversedNames)

// prints ["scylla", "muto", "kong", "godzilla"]

You can simply pass in the greater-than operator, and Swift will infer that you want to use its string-specific implementation.

Closures are Reference Types in Swift

Closures are reference types. That means when you assign a closure to more than one variable they will refer to the same closure. This is different from the value type which makes a copy when you assign them to another variable or constant.

A closure that captures the value of a variable is able to change the value of that variable.

Closures can capture and store references to any constants and variables from the context in which they are defined.

Scope and context are often confused. The scope is fixed because the code you write is fixed and defined. Context is fluid, and it depends on the execution of your code. So, you may have access to a property because it’s in scope, but because of the context of your code, i.e. its point in execution, that property is empty. You can see scope as to how your code is defined (fixed), and context as what your code does at any given point in time (fluid).

This is known as closing over those constants and variables.

let f1Countries = ["bahrain", "italy", "portugal","spain","monaco"]

func visitCountry() -> (String) -> Void {

var numberOfRaces = 0

return {

print("I just visited \($0)")

numberOfRaces += 1

print("Number of races covered: \(numberOfRaces)")

}

}

let bucketList = visitCountry()

f1Countries.map { $0.uppercased() }.forEach {

bucketList($0)

}

print("NOW I AM BANKRUPTED")

//finally prints one FACT.

The counter variable numberOfRaces looks like it is initialized with a value of 0 every time the visitCountry() function is called. However, due to the value capturing of the closure, its value keeps incrementing by 1, every time we call the closure. In other words, the bucketList closure captures the value of the numberOfRaces variable.

Swift handles all of the memory management of capturing for you. Swift is clever enough to know whether it should copy or reference the values of the constants and variables it captures.

Example: Create a new reference to visitCountry() and see the output.

let newList = visitCountry()

f1Countries.map { $0.uppercased() }.forEach {

newList($0)

}

/*Prints

I just visited BAHRAIN

Number of races covered: 1

I just visited ITALY

Number of races covered: 2

I just visited PORTUGAL

Number of races covered: 3

I just visited SPAIN

Number of races covered: 4

I just visited MONACO

Number of races covered: 5

*/

The assignment of visitCountry() to a constant newList will assign a new reference and the value of variable numberOfRaces is initialised to 0 in this new context. Test the example and see the output on the console for yourselves.

Assignment Example : Try the below code to see what the numberOfRaces current value is. It explains closing over the variable numberOfRaces.

let fewMoreCountries = ["azerbaijan", "canada", "france"]

var nextBucket = bucketList

fewMoreCountries.map { $0.uppercased() }.forEach {

nextBucket($0)

}

//This example will make things clear on closing over in a closure.

Escaping Closures

A closure is said to escape a function when the closure is passed as an argument to the function but is called after the function returns. In other words, it outlives the function it was passed to. An escaping closure is generally used in completion handlers since they are called after the function is over.

- non-escaping closure is a closure that’s called within the function it was passed into, i.e. before it returns.

Closures are non-escaping by default.

A secondary feature of escaping closures is that, whenever you refer to a property or method of self within the function body, the compiler will insist that you write self explicitly. That’s because such a reference captures self, and the compiler wants you to acknowledge this fact by specifying self explicitly.

An escaping closure outlives the function it was passed to.

In this sense there are two kinds of closures:

An escaping closure is a closure that’s called after the function it was passed to returns. In other words, it outlives the function it was passed to.

A non-escaping closure is a closure that’s called within the function it was passed into, i.e. before it returns.

There are several ways to escaping the closure:

Storage: When you need to preserve the closure in storage that stays in the memory, part of the calling function gets executed and returns the compiler back. (Like waiting for an API response).

Asynchronous Execution: When you are executing the closure asynchronously on the dispatch queue, the queue holds the closure in memory, to be used in the future. In this case, you have no idea when the closure will get executed.

A good example of an escaping closure is a completion handler. It is executed in the future, after a lengthy task completes, which implies it outlives the function it was created in.

Example : Using the same from Apple Swift documents.

var completionHandlers = [() -> Void]()

func someFunctionWithEscapingClosure(completionHandler: @escaping () -> Void) {

completionHandlers.append(completionHandler)

}

func someFunctionWithNonescapingClosure(closure: () -> Void) {

closure()

}

class SomeClass {

var x = 10

func doSomething() {

someFunctionWithEscapingClosure { self.x = 100 }

someFunctionWithNonescapingClosure { x = 200 }

}

}

let instance = SomeClass()

instance.doSomething()

print(instance.x)

// Prints "200"

completionHandlers.first?()

print(instance.x)

// Prints "100"

The someFunctionWithEscapingClosure(_:) function takes a closure as its argument and adds it to an array that’s declared outside the function. If you didn’t mark the parameter of this function with @escaping, you would get a compile-time error.

Autoclosures

An autoclosure is a closure that is automatically created to wrap an expression that’s being passed as an argument to a function. The closure itself doesn’t take any arguments, and when it’s called, it returns the value of the expression that’s wrapped inside of it. Simply put,

An autoclosure allows you to pass an expression to a function as an argument.

Example :

func noAutoClosure(_ result: () -> Void) {

print("Before")

result()

print("After")

}

noAutoClosure(print("Hello"))

// if the print method is not enclosed in curly brackets,

//the compiler throws below error

//Cannot convert value of type '()' to expected argument type '() -> Void'

noAutoClosure({ print("Hello") })

// this function call will work

//prints Before\n Hello\n After\n

func testAutoClosure(_ result: @autoclosure () -> Void) {

print("Before")

result()

print("After")

}

testAutoClosure(print("Hello"))

//the print("Hello") won't be executed immediately,

//because it gets wrapped inside a closure for execution later.

- It is primarily used to defer execution of a (potentially expensive) expression to when it’s actually needed, rather than doing it directly when the argument is passed.

When you call a function that uses this attribute, the code you write isn't a closure, but it becomes a closure, which can be a bit confusing – even the official Swift reference guide warns that overusing autoclosures makes your code harder to understand.

The @autoclosure attribute is used in Swift wherever code needs to be passed in and executed only if conditions are right. For example, the && operator uses @autoclosure to allow short-circuit evaluation.

Object Oriented Programming vs Functional Programming

- In object-oriented programming, you declare a class by defining its member variables and its methods (member functions) up-front.

- You create instances of that class and each instance comes with a copy of the member data, initialized by the constructor.

- You then have a variable of an object type and pass it around like a piece of data, because the focus is on its nature as data.

Example :

class MyClass {

var someClosure: ((_ someString: String) -> ())?

init() {

self.someClosure = someMethod

}

func someMethod(aString: String) -> () {

print(aString)

}

}

let instance = MyClass()

if let someClosure = instance.someClosure {

someClosure("My name is AAYUSH")

}

//prints My name is AAYUSH

- In a closure, on the other hand, the object is not defined up-front like a class or instantiated through a constructor call in your code. Instead, you write the closure as a function inside of another function.

- The closure can refer to any of the outer function's local variables, and the compiler detects that and moves these variables from the outer function's stack space to the closure's hidden object declaration.

- You then have a variable of a closure type, and even though it's basically an object under the hood, you pass it around as a function reference, because the focus is on its nature as a function.

Example :

var numArray = [3, 7, 13, 19]

let myClosure = { (number: Int) -> Int in

let result = number * number

return result

}

let squaredNumbers = numArray.map(myClosure)

print(squaredNumbers)

//the variable numArray is CLOSED OVER by the constant "myClosure"

The map method takes myClosure as an argument and calls the closure for execution. It then performs the steps inside the closure on each of the elements in the numArray integers and returns the result in to a constant squaredNumbers.

Whenever you assign a function or a closure to a constant or a variable like in the above example, you are actually setting that constant or variable to be a reference to the function or closure. In the example above, it’s the choice of closure that myClosure refers to that’s constant, and not the contents of the closure itself.

Advantages of using Closures in Swift

Closures are much less verbose when compared to Functions. Swift can infer the parameter types and return type from the context in which the closure is defined thereby making it convenient to define and pass to a function.

Swift Closure can be used to capture and store the state of some variable at a particular point in time and use it later.

Closures allow us to run a piece of code even after the function has returned.

One of the key advantages of closures in Swift is that memory management is something you, the developer, don't have to worry about.

Swift’s closure expressions have a clean, clear style, with optimizations that encourage brief, clutter-free syntax in common scenarios.

Swift's closures can be passed as input parameters to higher order functions and understanding the syntax can help you use them effectively while developing in swift.

Conclusion

Closures are an important concept, and you will use them often in Swift. They enable you to write flexible, dynamic code that is easy both to write and to understand.

Closures don't give you any extra power. Anything you achieve with them you can achieve without using them too. But they are very useful for making code more clear and readable. And as we all know clean readable code is a code that is easier to debug.

It was fun playing with closures and here is a github link to examples of closures and the variations in syntax. Most of them are collected from other blog posts I used to practice and understand closures.

Scope

The scope of an item in Swift represents the period of time for which the item is accessible within our program.

If you are relatively new to iOS development, chances are that you’ve already incorporated scope in your reasoning about your code, without knowing it! “Which variable can I access where?”

As such, the scope of the variable or constant is always a subset of the variable or constant's lifetime due to the fact that they exist in memory but may not be accessible. Essentially, the scope of an object defines the areas of our program from which the variable or constant can be accessed.

In Swift, the scope of variables, constants, and other named declarations can be subdivided into one of two general categories; top-level or global scope and local or nested scope.

- Global Scope.

By default, variables, constants, or other named declarations that are declared at the top-level of a source file are said to have a top-level or global scope. This means that they are accessible from code in any source file within the same module.

- Nested Scope.

Local or nested scope are subsets of the global scope and are generally nested within the direct scope of a variable, the variable is accessible in all of those scopes. Functions and methods form a new level of scope, as do closures.

I found this Article really helpful while reading about scope. Please refer to the same which gives a clear example to explain scope in Swift.**